Masks and Transplants

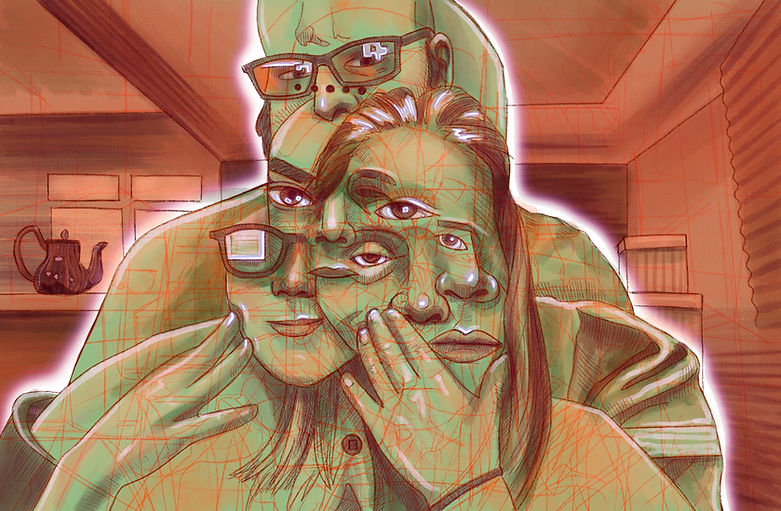

Emanating from a complex web of visual interaction, these portraits metamorphose from static documentation of digital communication into multi-faceted musings of what it means to be a community of connected minds. The process of overlaying and integrating these faces into a unified context reimagines portraiture as a shared experience and extension of empathy, rather than simply a depiction of facial anatomy.

For the purposes of engaging with specific concepts about the face and identity, I documented images of each of my classmates during our synchronous meetings and made simplistic drawings based on their portraits. I transplanted these images into a shared space and brought out specific details from the chaos. Lastly, I relied upon memory and a touch of alchemy to reimagine and reemphasize each individual’s unique features. The end result is an ode to this community built upon a desire to comprehend and value “the masks” that we all possess. Each unique feature reflects the identity and personhood of my classmates as we shared this intellectual space and communicated through digital interface.

In the preliminary stage of this project, I documented and simplified through rough sketches the visual features of each of my classmates’ faces. During our class meetings, I used my computer to screen shot images of my classmates and me in order to record our appearances and relative positions that day. I did not attempt to stage or control anyone’s image and in all but the first drawing my classmates were unaware of the moment when their image was being captured. I then cropped the images to the same size, which reflected the allotted rectangular spaces we were all granted within the video chat interface.

Once I had prepared the images, I quickly sketched out the general details and structure of each person’s features and their environment. These simplistic sketches are proxy for what I think of as “the mask.” Deleuze and Guattari describe how the face is the intersection between “significance” and “subjectification,” also referred to as the “white wall” and “black hole” system.[1] The cumulative result is that “the face is part of a surface-holes, holey surface, system.”[2]

[1] Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, “Year Zero: Faciality,” in A Thousand Plateus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 167.

[2] Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, “Year Zero: Faciality,” in A Thousand Plateus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 170.

My initial drawings emphasized and prioritized the structures surrounding the holes of the face and the perimeter of the face’s “surface” or “wall,” while simplifying and flattening the “volume-cavity elements of the head.”[3] In the same way that the surface of the face is a front for the biologically essential systems in the head (e.g. the mouth, sinus, brain, etc.), the face also functions as a front or mask for the identity of an individual. As Artuad describes, “All of this graphic and sonorous arrangement around the face indeed pertains to theater, an interior theater where a secret drama is now being played.”[4] Within this project’s context, the facial masks we all possess are transmuted into digital masks of physical masks, crisp shells that reflect and represent the tangible but distant facial features of each individual.

[3] Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, “Year Zero: Faciality,” in A Thousand Plateus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 170.

[4] Antonin Artaud, “The Human Face” in Antonin Artaud: Works on Paper (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1996), 91.

Once the preliminary drawings were complete, they were all layered upon and between the others and created a tangled and chaotic network of lines. The overlaying and intermingling of facial features vividly engaged with the ethical complications inherent in discussions surrounding facial identity. If, as Levinas states, “the face is meaning by itself,” was I compromising the individuality of my classmates or was their identity strong enough to withstand the metamorphosis?[5] Just as the “implications of donating a deceased loved one’s face to a stranger” should be treated with prodigious gravity, so must the translation and merging of others’ faces be dealt with respect and consideration.[6]

[5] Emmanuel Levinas, Ethics and Infinity: Conversations with Philippe Nemo, trans. Richard A. Cohen (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1982), 86.

[6] Brown et al., “Ethical Considerations for Face Transplantation,” in International Journal of Surgery (London: Elsevier, 2007), 358.

.jpg)

From the precise web of line work, I extracted details ranging from the subtle to the dominant. An eye, nose, or mouth would stand out from a motley conglomeration of lines and I would reinforce and bring it forward. As both an arbitrator and empathetic acquaintance, I sought out the moments that reflected my classmates’ characteristics. A balance of community and differentiation, these networks of features and acts of extraction marvelously reflected the complexities and intimacies of discourse and social communication.

The combined masks contained what Gombrich describes as “the crude distinctions, the deviations from the norm which mark a person off from others.”[7] In this case, a more fitting term than crude would be ‘condensed’ - simplified in the mind and through the act of representation. There is more at play here, however, since I invested my own image into the portrait. The interplay of facial features became something much more involved, more personal.

[7] Ernst Gombrich, “The Mask and the Face,” in Art, Perception, and Reality, (Baltimore: JHU Press,1973), 13.

.jpg)

Gombrich explains that, “the student of art can at least contribute one observation from the history of portrait painting which strongly suggests that empathy does play a considerable part in the artist’s response – it is the puzzling obtrusion of the artist’s own likeness into the portrait.”[8] The use of my own image in the portrait is not simply an act of involvement, but an exercise in empathy and an attempt to reduce the impact that physical distancing has had on this priceless community. Quite simply, the practice mitigated the emotional toll of physical absence.

[8] Ernst Gombrich, “The Mask and the Face,” in Art, Perception, and Reality, (Baltimore: JHU Press,1973), 40.

The final phase of the artistic process was to recreate and weld together the facial features through a combination of memory and alchemy. The composition solidified and morphed into a space of combined presence. Gombrich made an intriguing assertion by claiming that, “Many of us would be unable to describe the individual features of our closest friends, the colour of their eyes, the exact shape of their noses.”[9] Although we may be able to identify them out of thousands of other faces, we are not able to completely and accurately remember and picture what they look like. Accurate memories of their appearance fade under the strain of physical separation and time spent apart.

[9] Ernst Gombrich, “The Mask and the Face,” in Art, Perception, and Reality, (Baltimore: JHU Press,1973), 8.

I wanted to incorporate this idea as a challenge for this project and, consequently, I worked on filling out the details and shading of the drawings without referencing any photos. Sometimes I would forget whose eye or nose I was drawing and would contemplate how to distinguish one known face from another. With each drawing, I became more familiar with the way a certain person’s mouth or eyelid curved or how their hair or neck framed their unique jawline.

When choosing the color palettes to use, I stayed relatively true to the color combinations that I use in my abstract paintings and felt that this fit the spirit of the portraits as well. These virtual incarnations of my classmates brought life to Taussig’s reasoning that, “A new reckoning has been born, more virtual than real, even while the old reality lingers, it being the human body that combines the real with the superreal.”[10] The act of drawing combined with the assertion of facial identities became a sort of “alchemy” and “metamorphosis” into a new entity, a kind of visual community.[11]

[10] Michael Taussig, Beauty and the Beast (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 40.

[11] Ibid, 11 and 40.

.jpg)

As this project progressed and as I continued to read more, two additional ideas characterized the work. The first is that the identity of each individual extended through their faces and beyond, into their environments and surroundings. “It is precisely because the face depends on an abstract machine that it is not content to cover the head, but touches all other parts of the body, and even, if necessary, other objects without resemblance.”[12] This statement is primarily why I chose to include items from each person’s surroundings. These items and environmental objects activate the spaces around the communal portraits. The addition of hands and shoulders appears natural as they support and contextualize the masks we each possess.

[12] Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, “Year Zero: Faciality,” in A Thousand Plateus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 170.

The final addition worth addressing was the inclusion of design elements from the video calls ranging from personal icons, to buttons in the interface, to messages and the luminous yellow box outlining the person who was speaking. Taussig makes the observation that, “Just as your face and body root your identity, so of course does your name.”[13] With the advent of digital, video communication these other markers have become additions to each person’s visual identity. They are hallmarks of interactive presence and, as such, I gave them a place of importance in the portraits.

[13] Michael Taussig, Beauty and the Beast (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 116.

Despite our physical separation, this community of connected minds continues to exist collectively in the symbolic, shared spaces of these portraits. Over the course of the semester we were able to bond through discourse regarding our experiences, both intellectual and experiential. Though imperfect and a mere reflection of our time spent together, this project allowed me to continually extend empathy to my classmates and the unique personhood they each possess. The face is an illusive concept that many have attempted to decipher, but through this practice I had the incredible opportunity to behold and meditate upon the identities of my colleagues, reflected within their unique and intrinsically valuable masks.